THE FLOWING

Notes on Historical Recipes for Past-Present-Future Relations

As one part of the project we look towards pre-industrial dye recipes since knowledges from the past might inform us to build alternative presents and futures. During the making we follow our sensory and affective responses. We activate our bodily knowledges and reconsider knowledges of our ancestors. What kind of understanding does these recipes hold? What is transferable, what is lost?

# Isatis Tinctoria (European Indigo) / Indigo Ferata

We know the colour Indigo, more than anything, from the blue of our jeans. Yet, presumably the oldest known vat dye, it carries the weight of colonial history. As anthropologist Michael Taussig sums up: “How much more cruel has been the not-knowing and the forgetting, such that we could have no idea of the long march from a plant in a far-away field in the tropics to its ultimate fate in a vat and then in a market auction in Calcutta or London as a cake of color? Can we re-trace the steps?” (Taussig: 10)

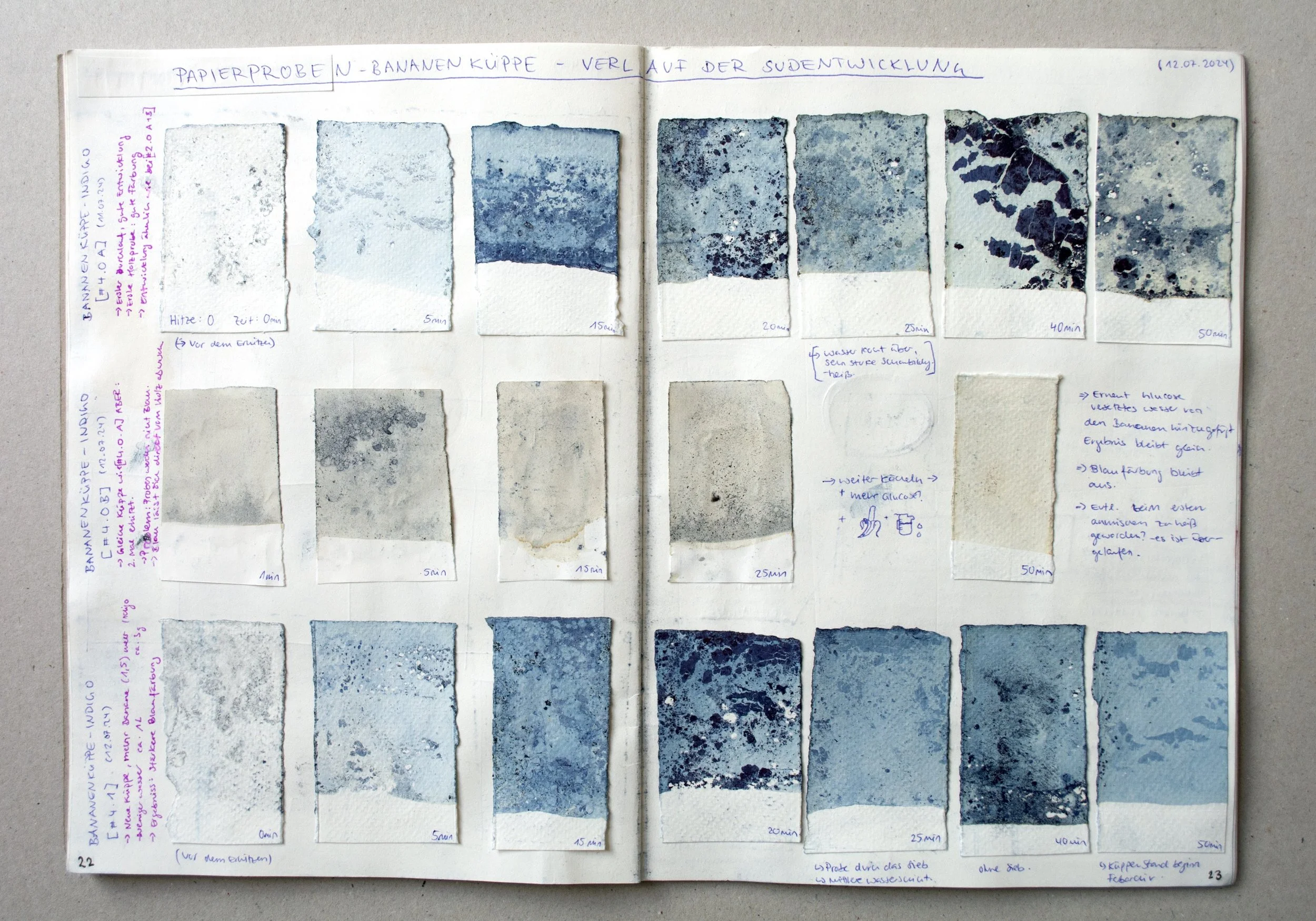

In following traditional recipes we experience the vat dyeing process, its difficulties and sensory effects. Observing the transitions of the colour while processing the vat and being in contact with oxygen is just one part of a complex recognition. A traditional vat is a well acid-balanced fluid inhabited with bacterial cultures. They multiply, eat and digest. This is the necessary environment to transfom the colour from plant to dye on a molecular scale. In modern times chemical additives accelerated or even replaced the bacteria in vat-dyeing. Bacteria were too demanding for industrial production in high speed. But vat-dyeing is - and always has been - an overwhelming smelly, sweaty and ‘dirty’ process. The skin, the sense of smell and the tools we employ are involved and stained afterwards. But the reward is a deep, intense blue, at times almost black, gained through layering of colour and experiences.

It also takes a complex proceeding to gather pigments from the growing plant. The plant communicates its content of colouring potential in several ways- the colours of the stem and leaves change slowly after the blossom, some leaves start to roll up and turn from green to violet. Some leaves just turn yellow but still hold a high amount of indicatin, a pre-level of indigo in chemical classification. Also the intensity and grade of colour differs from plant to plant though they were exposed to the same weather conditions and location in the garden. The stunning labour of becoming- from seed (planting, watering, growing, harvesting, processing and applying) to colour- results in new perspectives of entanglements and habits concerning our environment.

# Rubia Tinctorum (Madder)

The saturated, ramified root of the Rubia tinctorum is filled with Alizarin pigment. Since ancient times Rubia tinctorum, known as madder, or madder root, played a central role as a dye plant. In European culture it has been sold for medical or colouring purposes for thousands of years. Emperor Charlemagne brought it to Aachen and with the help of madder the region became more wealthy and prosperous. After the rise of synthetic colours it disappeared from the fields. Nowadays just bewilderd plants live here. They are mostly regarded as insignificant weeds.

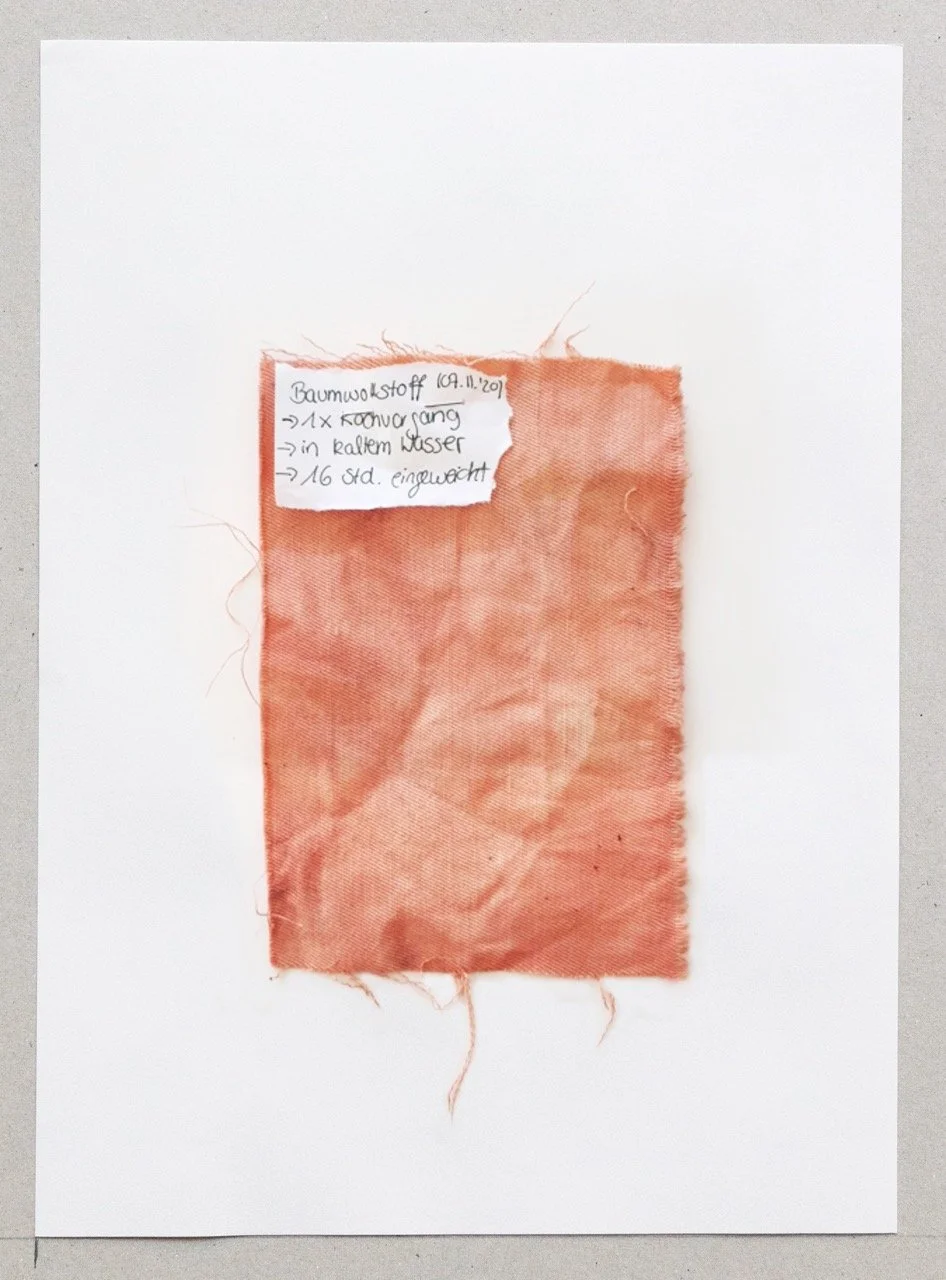

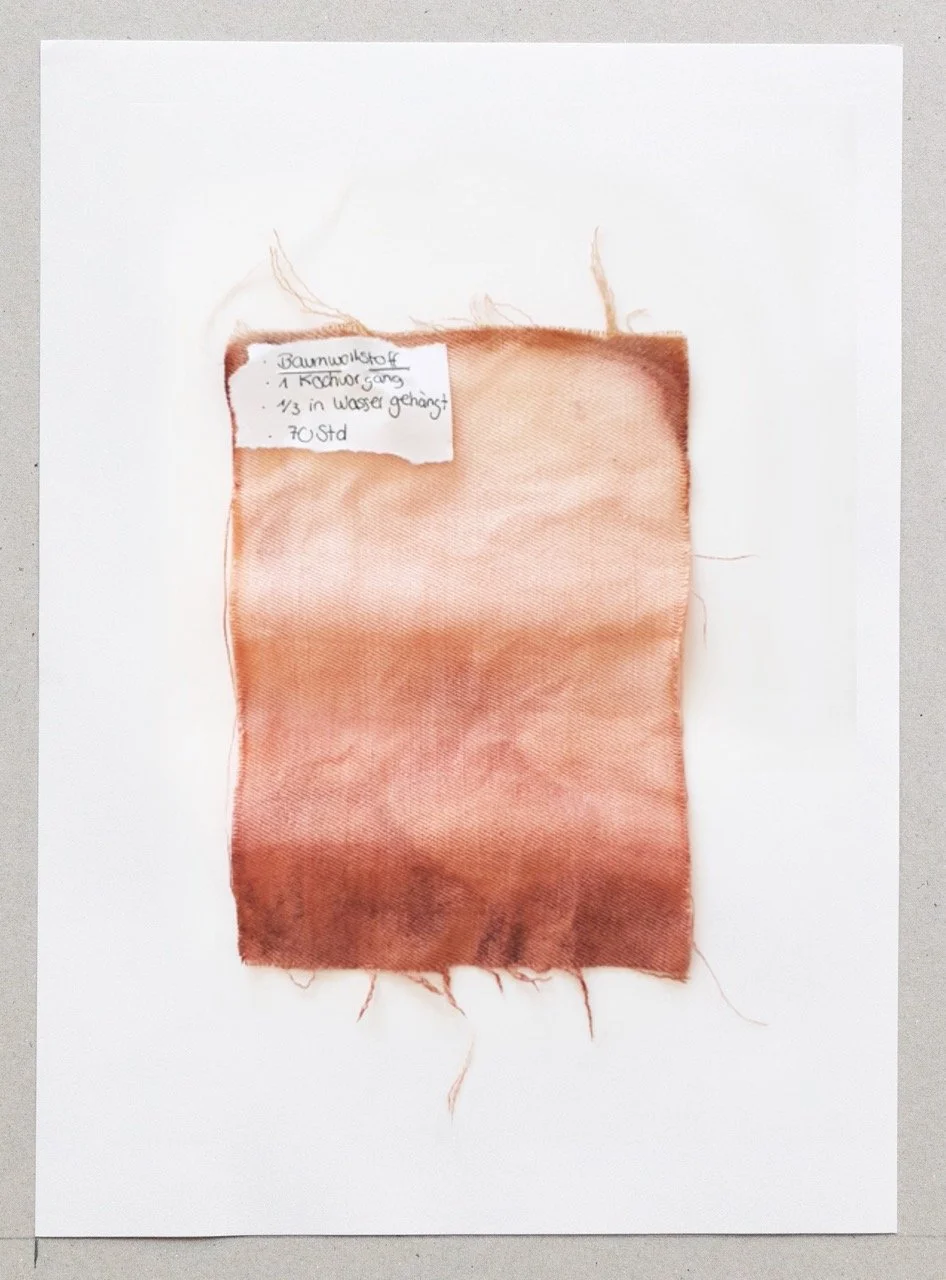

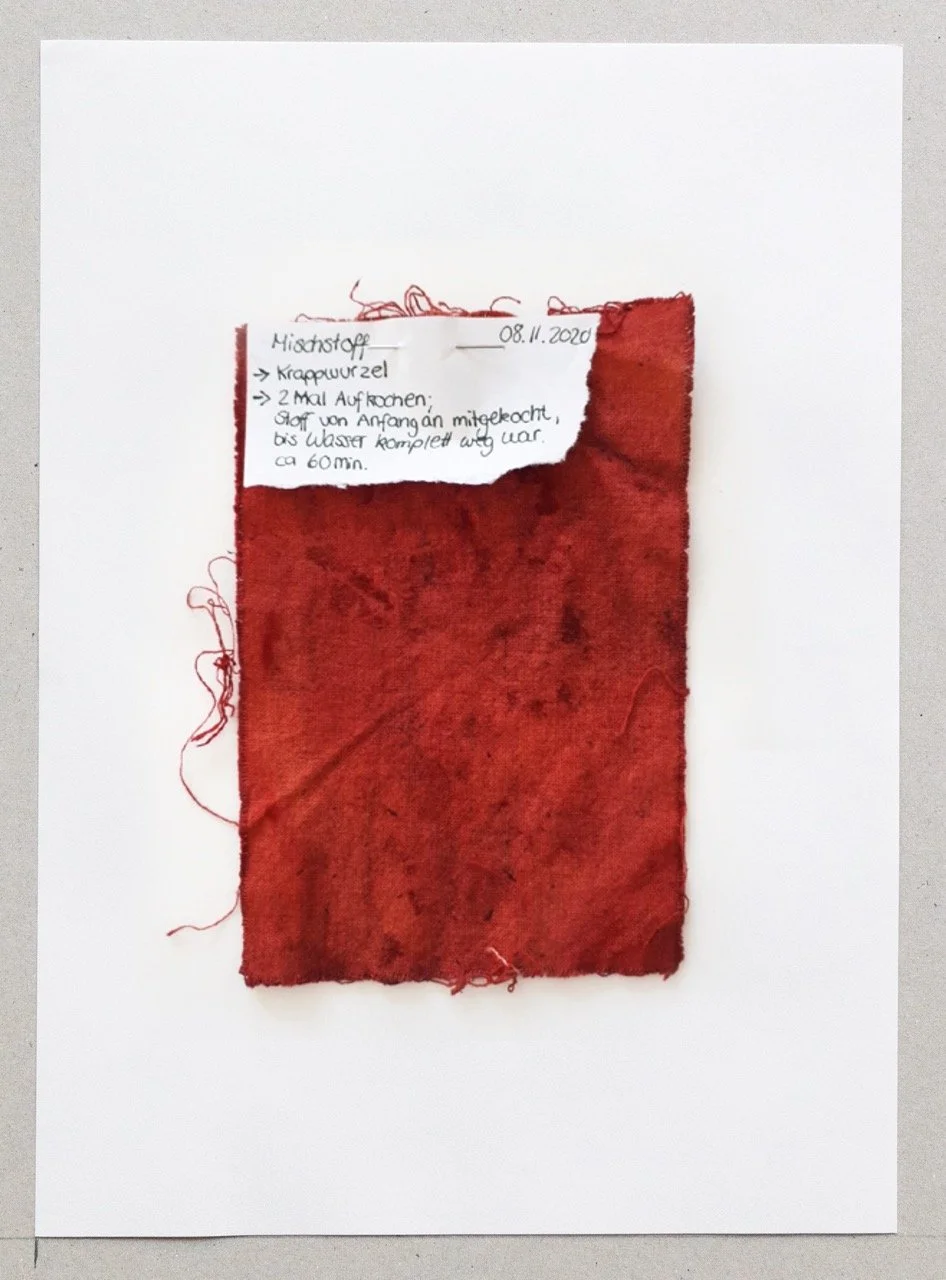

Compared to Indigo the process of harvesting colour from madder root is simpler. We work with the dried roots, harvested in the Charlemagne- Botanical Garden of the Aachen University, and follow historical recipes. The results differ in a wide range of shades and intensities of red, orange, pinkish and brown. Water, temperature, type of textile, type of mordant, time and the concentration of the dye bath all play a part. Its smell is kind of sweet and mild.

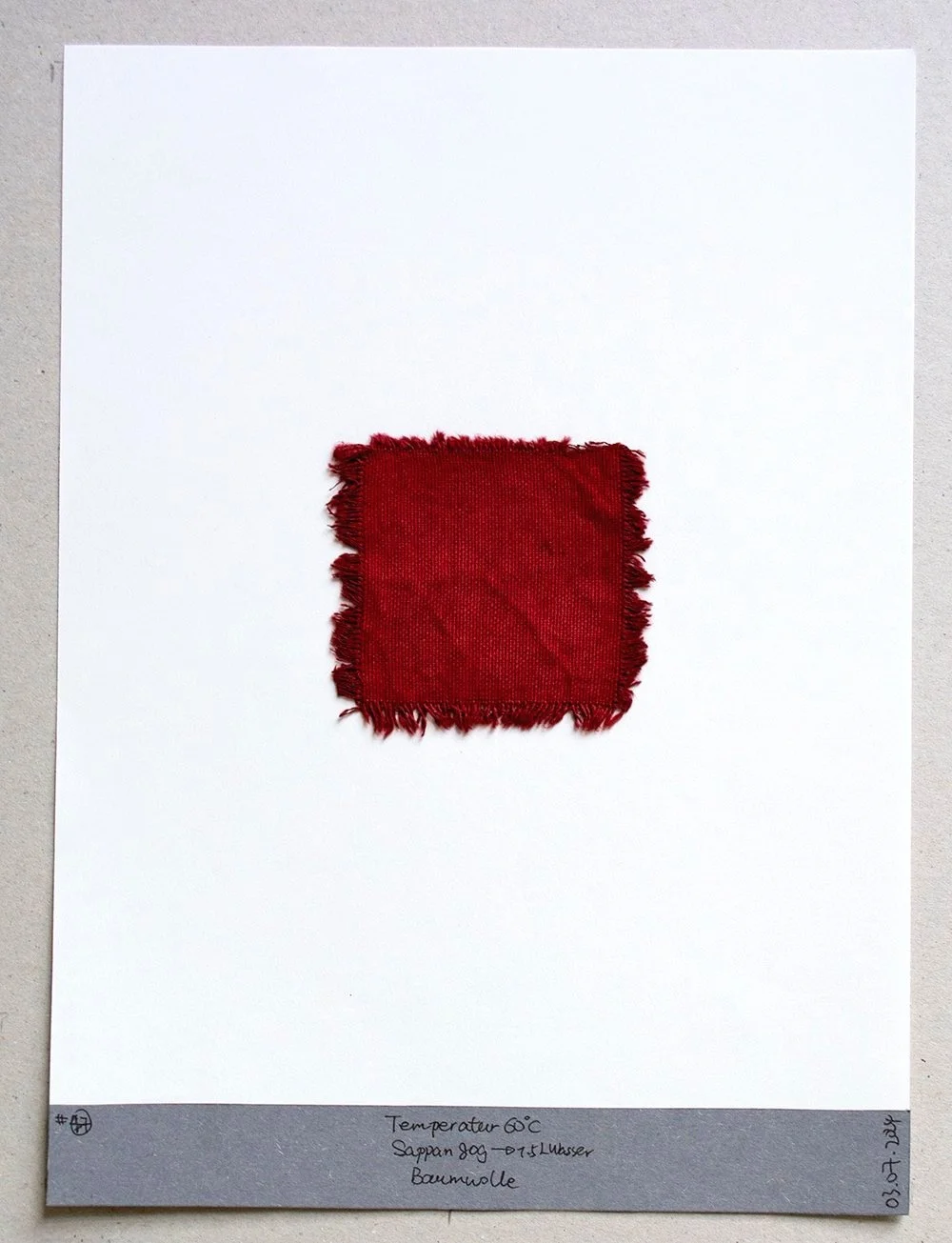

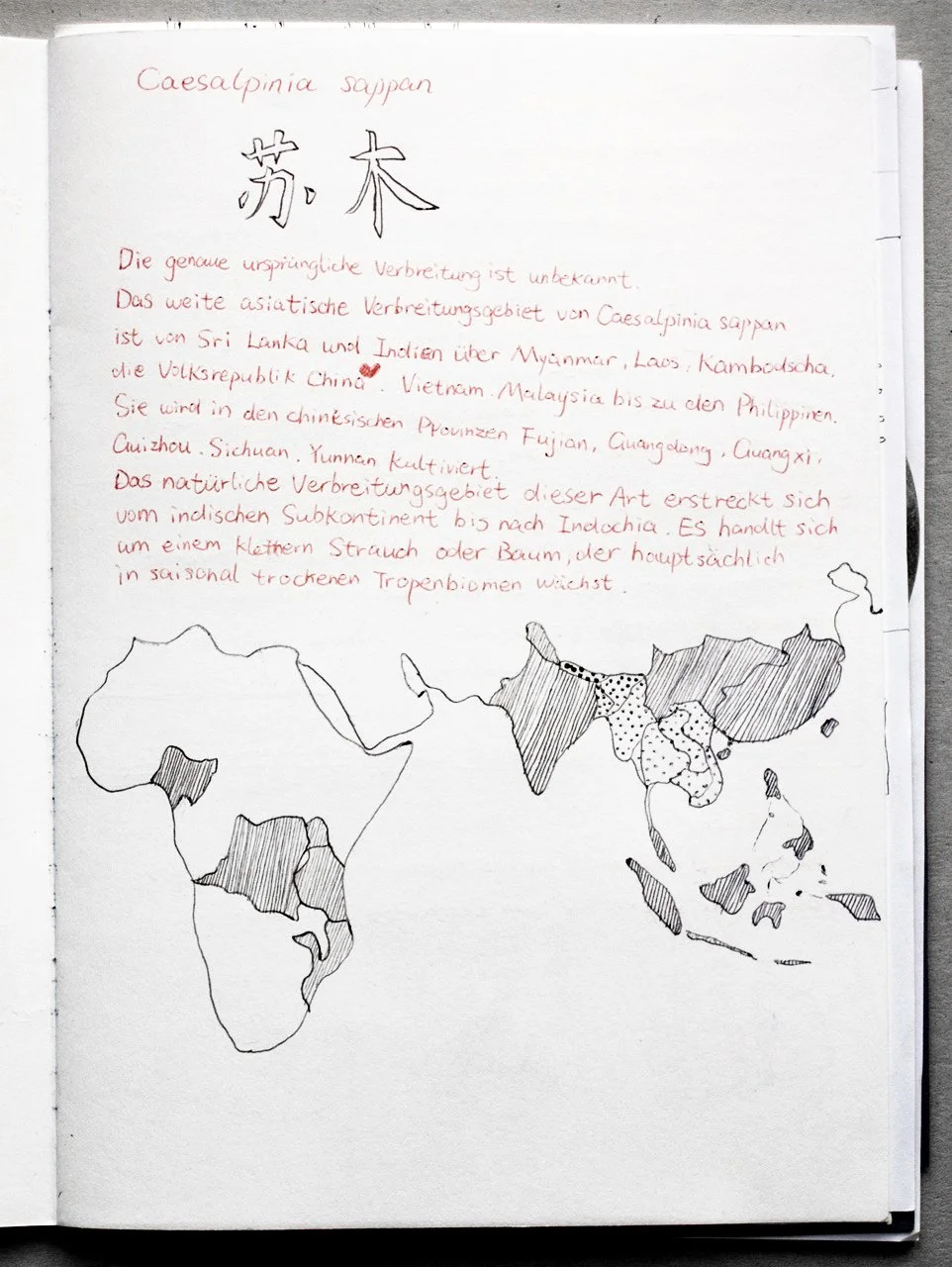

# Caesalpinia Sappan (Sappan Wood)

One of our student collaborators Ziqing Guo brought Sappan wood from one of her visits home in China. Sappan Wood is mainly distributed in tropical Asian regions and has been locally and historically employed as a dye and medicinal plant. The colouring agent stemming from the wood first appears in yellowish hues and later through oxidation can shift to amazingly deep reds. Further, mordants and ph, temperature and cloth, the soil in which it was grown all take part.

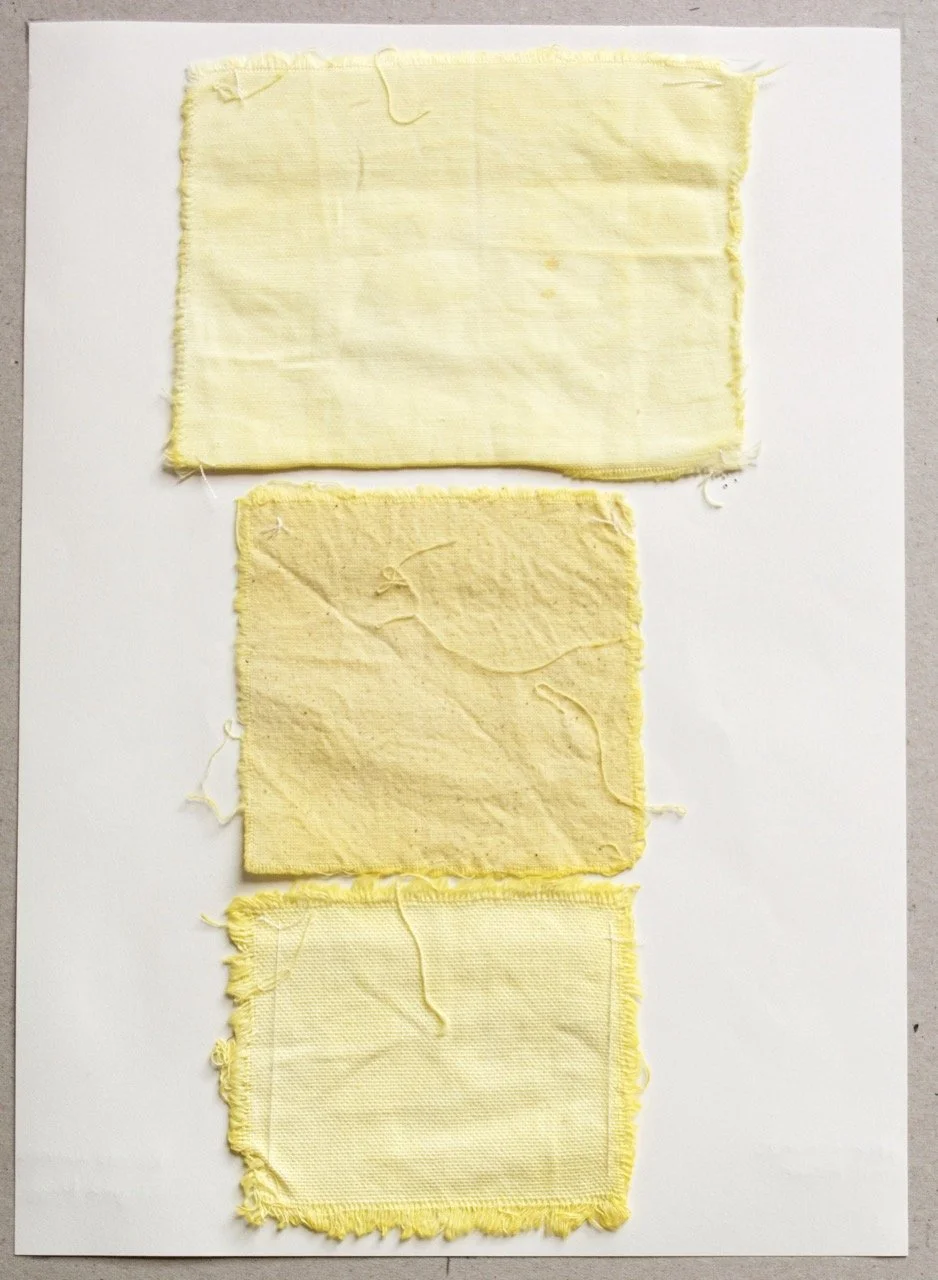

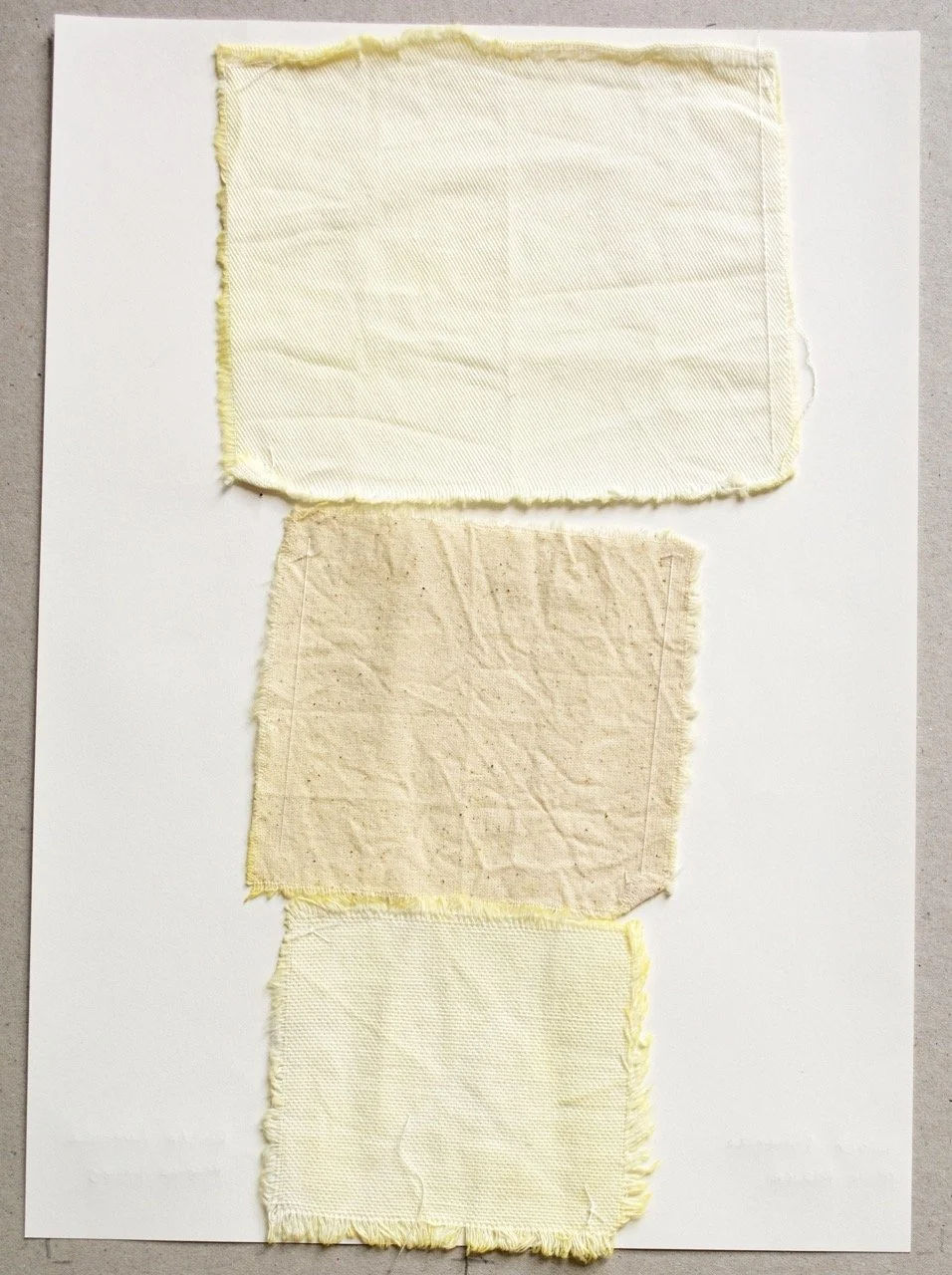

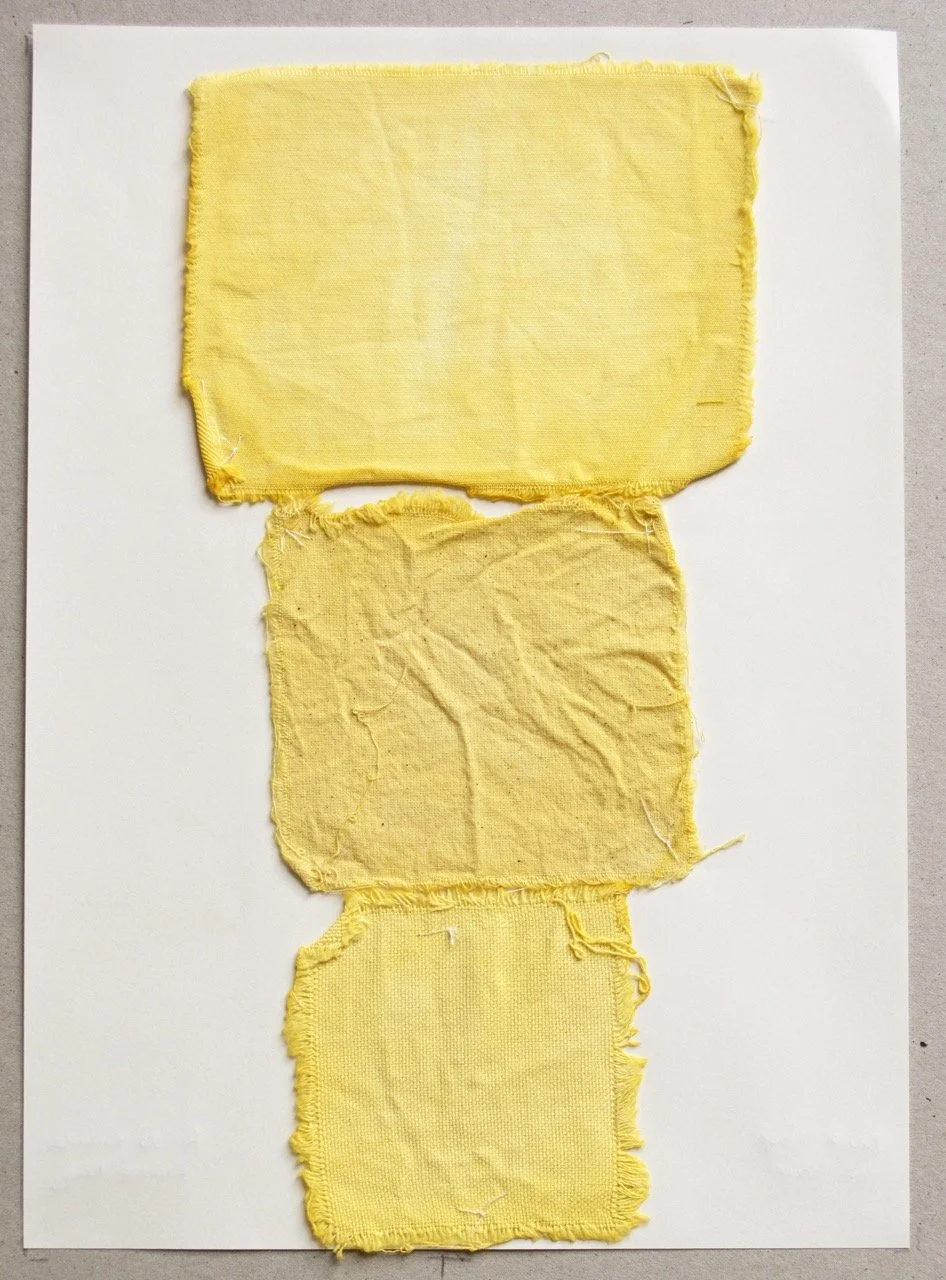

# Reseda Luteola (Dyer’s Weed)

The Reseda dyer’s weed was this year ready to harvest from our garden. Native to Europe and Western Asia, it prefers sandy dry soils to moist and rich. Its colouring agent is called Lutein, part of the Carotene family, and is one of the most resilient and lasting organic yellow colouring agents with first records dating back to 8000 BC.

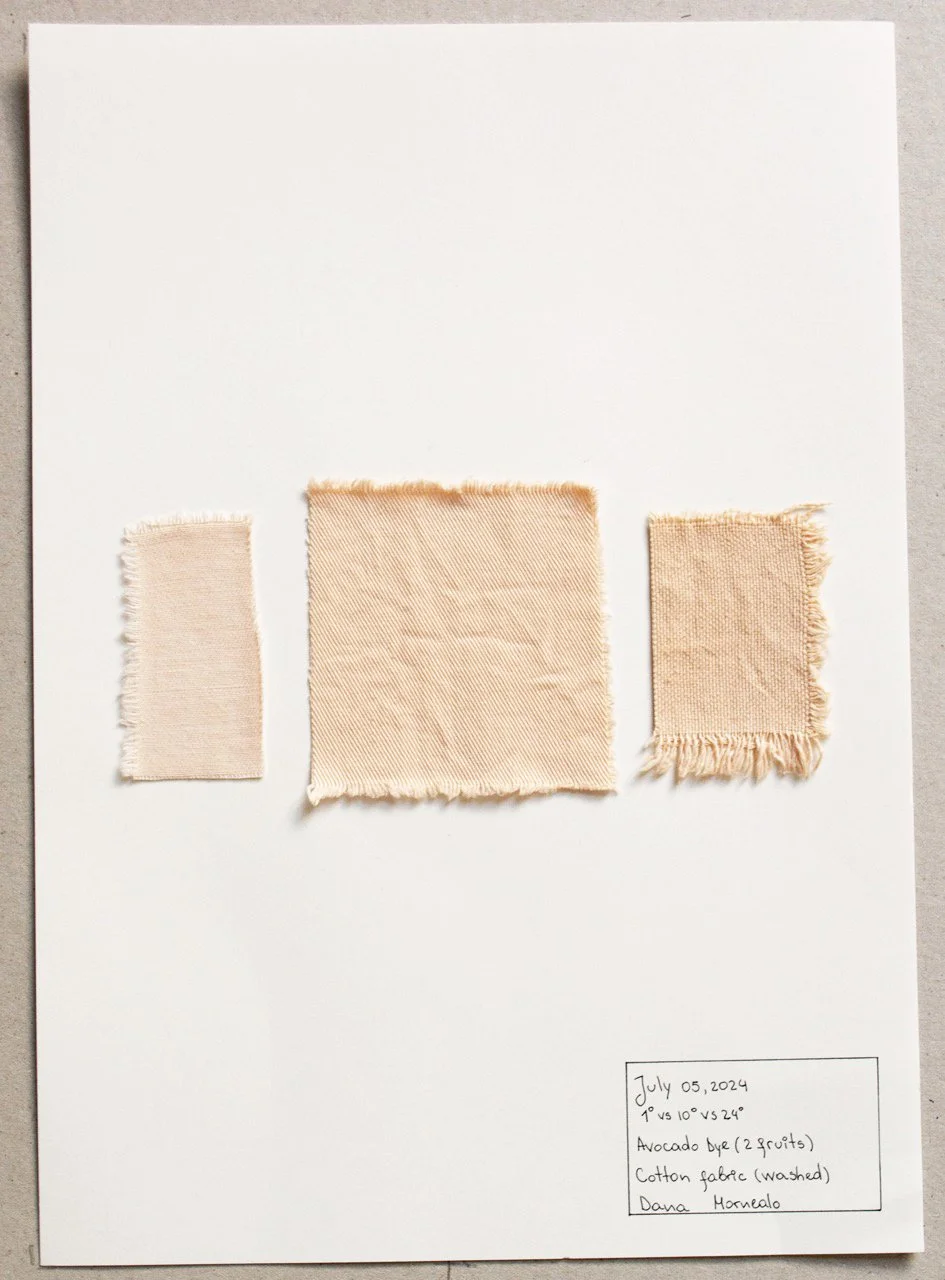

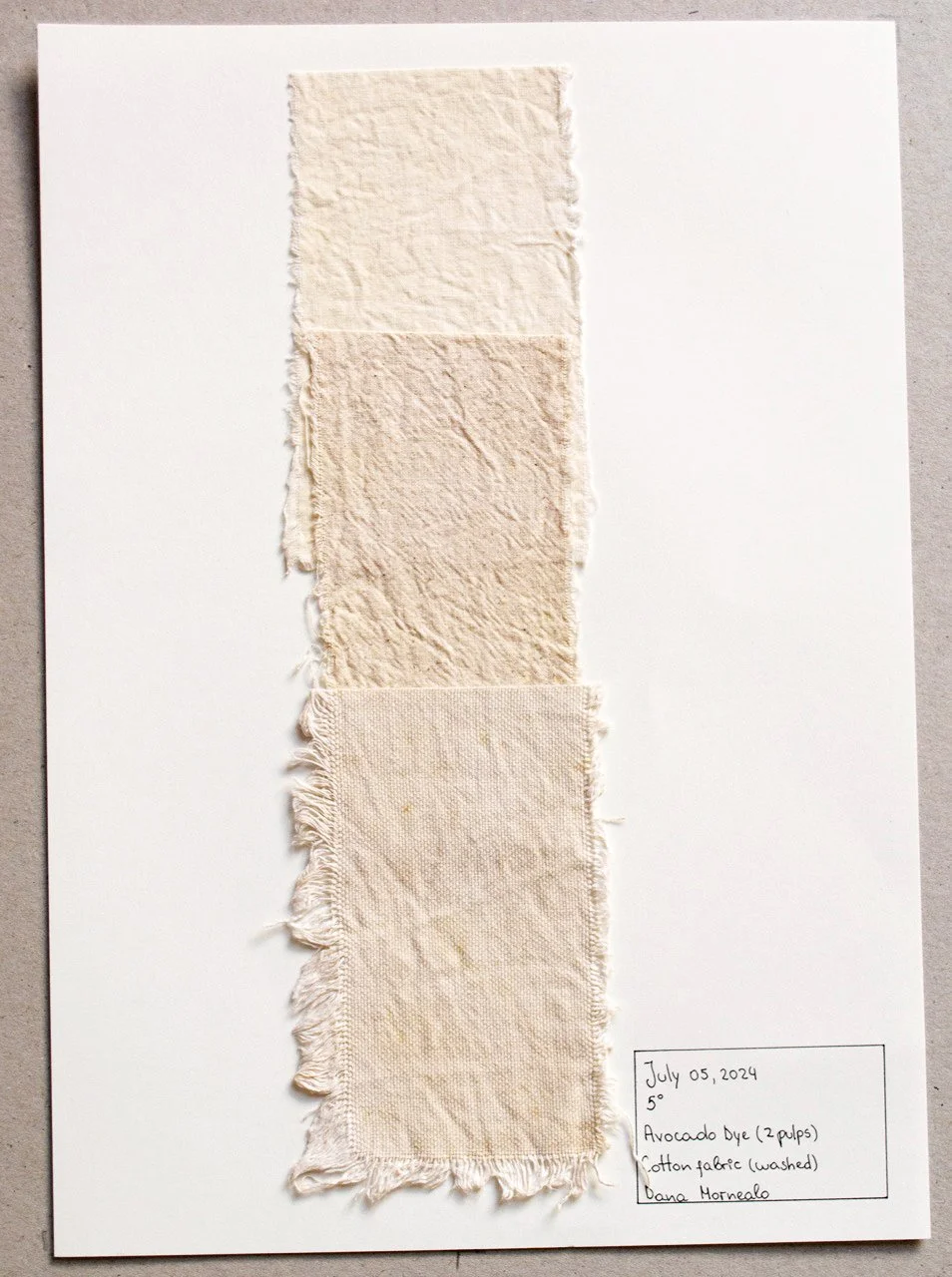

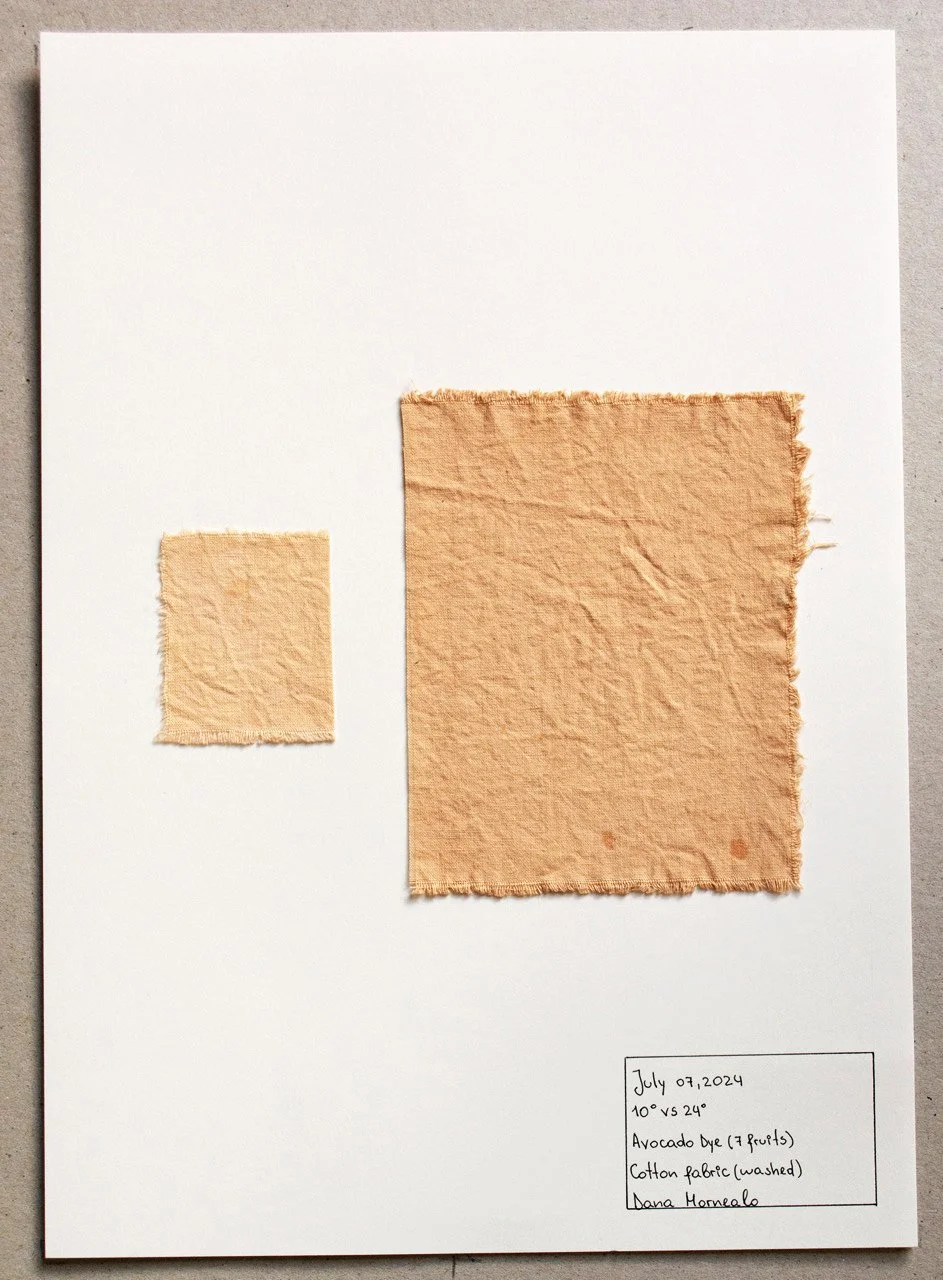

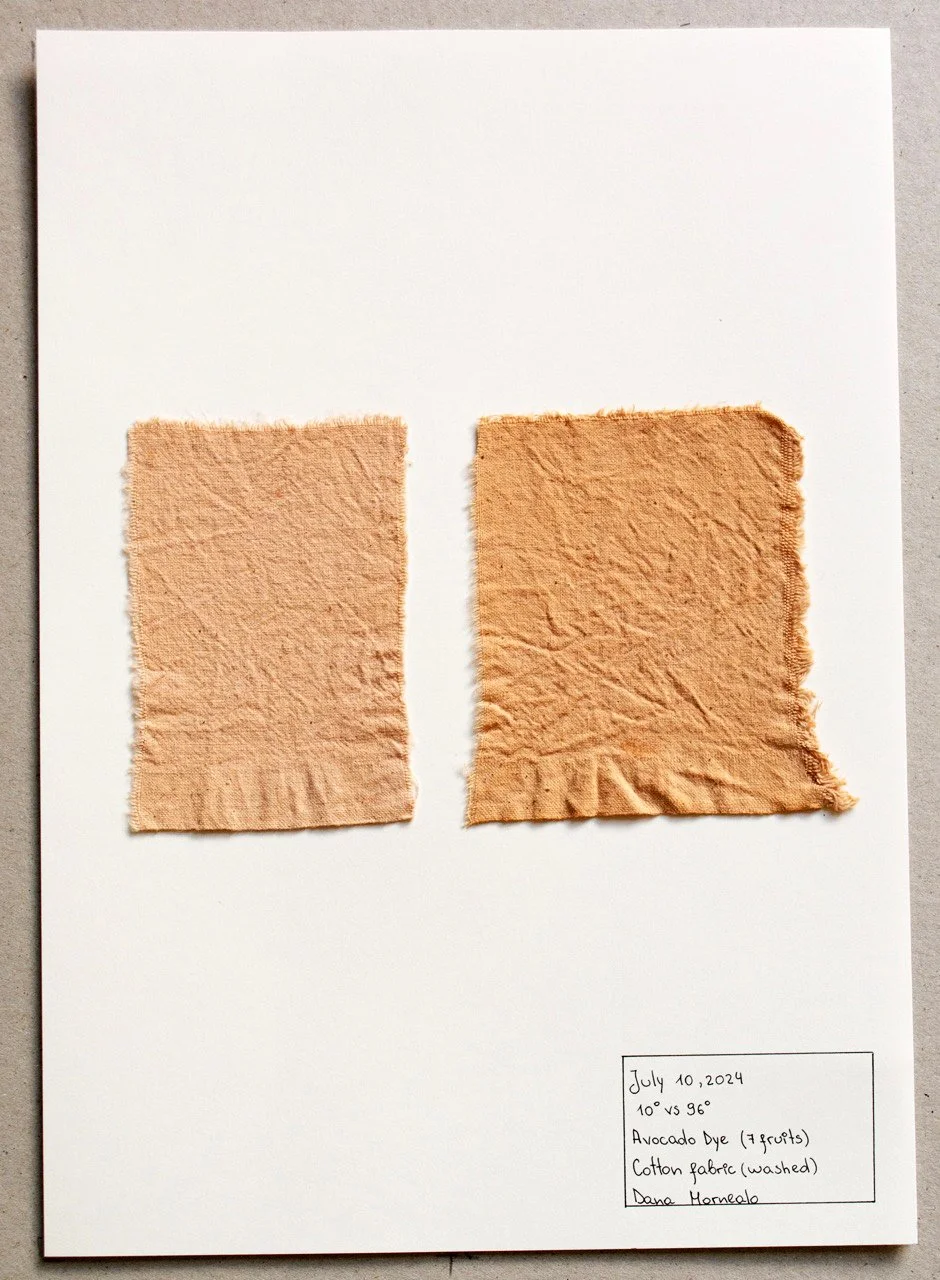

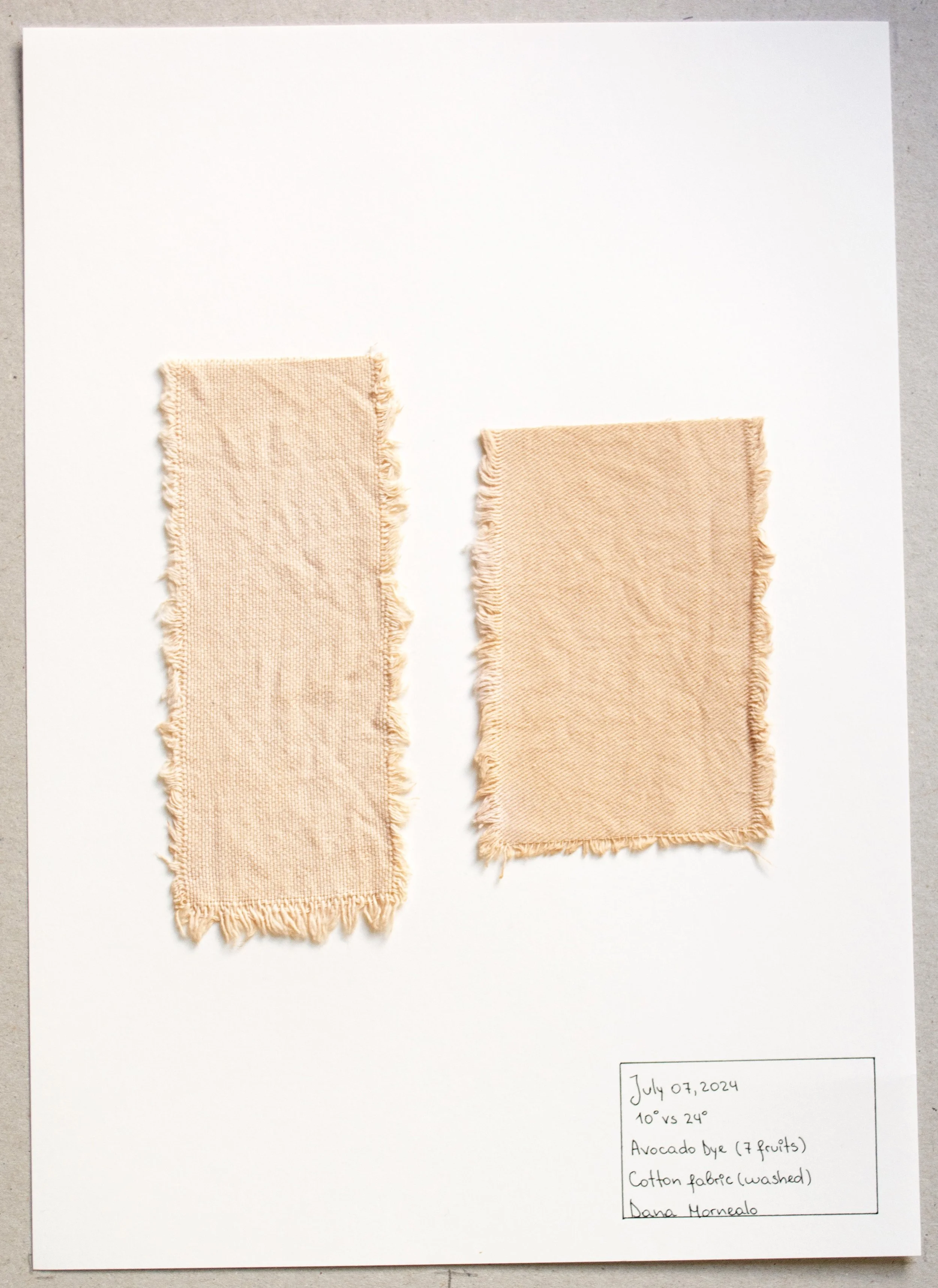

# Avocado Stones

One of our student collaborators Dana Monealo brought avocado stones from the avocado tree grown in her family home in Portugal. The skin and seeds (pit) of avocado both have been used for centuries for their richness in tannins and the tannic acid included luckily already serves as a mordant.